Beyond ‘Opium’: Marx, Religion, and the Struggle for Real Liberation

A short analysis of Marx’s famous passage, and what it means for us today

What did Marx mean when he called religion the opium of the masses?

And what does it mean in a world where organized religion is dwindling, while personal spiritual beliefs and atheism are on the rise?

This article is an attempt to answer those questions and clarify an often misunderstood passage of Marx’s philosophy, that has firmly taken root in the mainstream.

On a personal note, it is also an excuse to talk about one of the more poetic sections of Marx’s early writing and the powerful sentiment for genuine human liberation at the heart of Marxism.

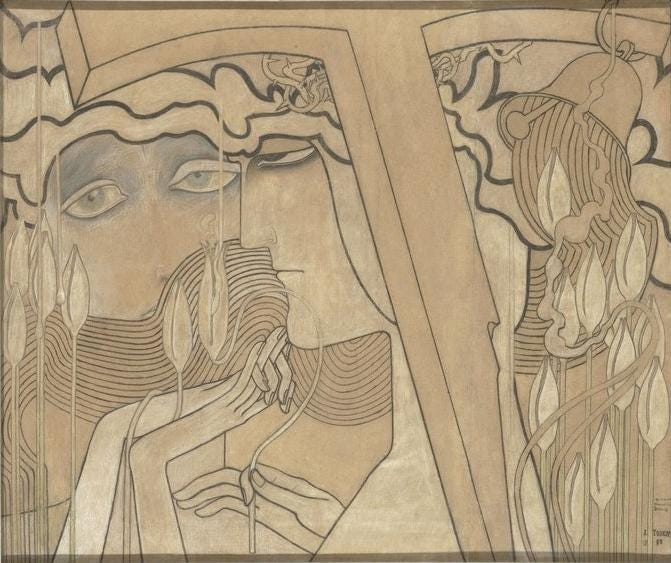

We all need a little beauty when the real world has often been stripped of it

The Context

The famous passage comes from the “early Marx”, as some thinkers and historians would call his pre-1848 political philosophy. In fact, 1843's “Critique of Hegel’s Philosophy of Right”, the origin of the quote, is often considered the first major work of the Marxist canon.

This is the Marx who had been a keen student and critic of Hegelianism, but had not fully concluded that Hegel ‘stood on his head’. This step would only be realized later, by completely abandoning Hegel’s transcendental idealism and grounding his ideas in a materialist analysis.

This text is a major part of that process.

In the relevant section, we can see Marx reflecting on the origin and meaning of religion, and how he is already drawn to a materialist analysis of the question.

Importantly, it isn’t so much a critique of religion, but rather a critique of the world we all live in, and what landscapes of meaning it produces. Something far more interesting in my opinion.

Let’s get to it then.

The Quote

Marx begins:

“The foundation of irreligious criticism is: Man makes religion, religion does not make man. Religion is, indeed, the self-consciousness and self-esteem of man who has either not yet won through to himself, or has already lost himself again. But man is no abstract being squatting outside the world. Man is the world of man — state, society. This state and this society produce religion, which is an inverted consciousness of the world, because they are an inverted world. Religion is the general theory of this world, its encyclopaedic compendium, its logic in popular form, its spiritual point d’honneur, its enthusiasm, its moral sanction, its solemn complement, and its universal basis of consolation and justification.”

Several things are established in this somewhat complicated introductory passage, that are important to understand.

To start with, Marx establishes that “Man makes religion, religion does not make man”. For him, it is something that doesn’t exist outside of the human consciousness.

At the same time, human beings never exist outside of their social context — to a degree that is what makes them human. So really, religion is produced by the society that human beings find themselves in. It is a response to their real conditions.

What sort of religion does this society produce? According to Marx, it is “an inverted consciousness of the world”.

What is meant by this, is that religion represents a counterpoint to all that is perceived to be wrong with this world:

The world is full of injustice? Justice will follow in the beyond.

The world is full of inequality? Under God, we are all equal.

Critically, this already shows just how connected the transcendental ideology of religion is to the material world. It just inverts its conditions, to act as “consolation and justification”.

Marx goes on:

“Religious suffering is, at one and the same time, the expression of real suffering and a protest against real suffering. Religion is the sigh of the oppressed creature, the heart of a heartless world, and the soul of soulless conditions. It is the opium of the masses.”

Here comes the famed passage, but what precedes it is just as — if not more — important.

Marx establishes firmly that religion in itself is not irrational, but rather a response to the real conditions, the real suffering, human beings face every single day.

Our time and Marx’s time have something fundamental in common. The all-encompassing social relations established by capitalism. And these social relations have stripped daily exploitation of all glitz and glamor.

A few hundred years ago, the serfs toiled in the field while the nobility and clergy ruled, all sanctioned by the divine.

Under capitalism, all of these decorations are gone. The capitalist class does not rule because they hold a divine right; they rule because they have the power to do so, which we justify with our own mythology. More on this later.

In this “heartless world” religion and transcendental ideology act as a painkiller, which is the core of what Marx meant by “opium of the masses”.

It isn’t a drug that is being fed to the population, it is an escape from the reality of conditions that are difficult to bear otherwise.

The conditions of society produce religion. The material produces the transcendental.

Marx concludes:

“The abolition [1Aufhebung, see below] of religion as the illusory happiness of the people is the demand for their real happiness. To call on them to give up their illusions about their condition is to call on them to give up a condition that requires illusions. The criticism of religion is, therefore, in embryo, the criticism of that vale of tears of which religion is the halo. Criticism has plucked the imaginary flowers on the chain not in order that man shall continue to bear that chain without fantasy or consolation, but so that he shall throw off the chain and pluck the living flower.”

For me, this is the key passage, that is sadly often overshadowed by its more famous counterpart.

What Marx describes here is the actual essence of his criticism, which isn’t so much concerned with religion itself, but rather the root cause of religious escapism.

Any criticism of the opiate is more importantly a “call on them [the people] to give up a condition that requires illusion”. This is the remarkable connection between the material and the transcendental.

If we accept Marx in his conclusion that religion is born from real concerns and exists in direct relation to real suffering, there is no way to overcome it without overcoming the suffering itself.

What follows is what I consider to be one of the most evocative passages in all of Marx’s work. Plucking the flowers from the chain, so it can be seen for what it is, and throwing it off.

This is the core demand and the humanity at the heart of the Marxist critique: Exposing the realities of society in all their horror, so people can find a path toward liberation.

What Marx offers here has nothing to do with a refutation of religion. It is a call for people to not just look at whatever they believe awaits them in the afterlife, and quietly ignore their current suffering.

Instead, they should look at society and judge it by its own merits, independent of the ideological concepts that have been built up over centuries to justify it.

It is a critique of class society and the flowers it needs to grow to hide the chains.

The Meaning

I am an atheist, and I have been for a very long time.

My family was only religious in the sense of vague cultural traditions, and occasional Christmas and Easter church services we attended to console my grandmother.

I can’t remember a time when I genuinely believed in a god, or anything spiritual for that matter.

As a teenager, this got me an over-inflated sense of ego and a vague contempt for genuinely religious people. In my view, this is the worst kind of atheism.

Organized religion has done plenty of damage, and continues to do so, but in the end, it is just one transcendental ideology among many. Religion has also done plenty of good and continues to offer consolation, hope, and meaning to people all over the world. Who am I to dismiss them for it?

I was inspired to write this piece by an excellent article by Ashely L. Crouch about capitalist ideological concepts becoming their very own opiate of the masses, and could not agree more.

When people use Marx’s quote to dismiss religion outright, they miss the essence of his writing.

As discussed above, Marx concludes his argument with the demand to “pluck the living flower”. What is that, if not an appeal to look at the world with clear eyes, and not be satisfied with the stories we tell each other, about how all is well in heaven and on earth?

These stories take many forms and most of them aren’t of religious origin.

In fact, an all-too-common form of today’s atheism is one of those stories. It rejects religion as the ghost of an anti-rationalist instinct, that we should have long overcome.

In this, it makes two critical mistakes, which Marx already identified in his 1843 text.

On the one hand, it dismisses all social contexts and replaces them with a vague notion of thinking “rationally” about these things. In this, it misses the crucial point, that our ideas don’t just magically manifest in our brains, but are the sum total of our life experience. Remember, the material produces the transcendental.

The most common outcome is an offputting and unfounded arrogance, the same I fell victim to many years ago. The worst-case scenario is the repackaging of racist and xenophobic tropes as “enlightenment ideas”. This is in particular weaponized against Islam, and the Arab world in general, these days.

On the other hand, this kind of atheism has its own transcendental ideology — the idea of an objective scientific methodology, that exists outside of social relations.

While the scientific method — or rather the different ideas that define that term — is undoubtedly an achievement, we should never forget that it can’t exist independent of our social relations, and all the issues that come with them.

Less than a century ago, eugenics, phrenology, and other forms of “race science” were widely accepted by the Western scientific community, not because they had any merit, but because they re-inforced the ideological foundations of white supremacy and imperialism.

There are similar examples of seemingly “objective” results, tainted by their social context, today. You only have to look at the state of economics in our university system, practically designed to serve the interests of capital and the job market.

Giving up one opiate for another doesn’t bring anyone closer to seeing the world with clear eyes. If anything, this form of unreflected rationalism is even better suited to the capitalist mode of production, because it abandons all visions of fundamental change.

Conclusion

In the same year “Critique of Hegel’s Philosophy of Right” was published, Marx wrote a letter to his longtime friend and fellow philosopher Arnold Ruge, discussing his ideas regarding Hegelianism.

In this letter, he outlined the central intentions of his methodology, which would eventually become the driving principle of the Marxist method:

“If we have no business with the construction of the future or with organizing it for all time, there can still be no doubt about the task confronting us at present: the ruthless criticism of the existing order, ruthless in that it will shrink neither from its own discoveries, nor from conflict with the powers that be.”

This is something I personally aspire to, and is in many ways the reason I write articles about Marxist ideas.

If the goal is genuine human liberation from the many systems and power structures that hinder us, the criticism of those in power must be ruthless.

But that very same criticism, devoid of all social context and losing sight of the actual goal of liberation, can only be impotent and ultimately useless.

What is the point of criticism of religion and other transcendental ideologies, when the goal isn’t to make the material world a better, more humane place? There is nothing noble or “rational” about crushing the flowers on the chain when we can’t point a way toward striking off that very same chain.

Religion was — and sometimes still is — an opiate of the masses, but our task isn’t to abolish the painkillers.

It is to put an end to the pain’s source.

The excerpts for this article are from Joseph O’Malley’s 1970 translation of “Critique of Hegel’s Philosophy of Right”, which usually does an excellent job of replicating Marx’s meaning and prose. But here “Aufhebung” is translated as “Abolition”, which is not quite correct. “Abolition” implies an active process, while “Aufhebung” is a Hegelian term, that implies a dialectical process, which will eventually “transcend” the current contradictions. Meaning, religion is not abolished, but rather overcome by societal development in this context.

Enjoyed this article? Want to support my work? Consider subscribing or buying me a coffee!